by Valarie lee James, Sky Island Alliance Adopt-a-Spring volunteer

“Darwin’s manner of deep watchfulness allowed the ordinary ground of life to become sanctified, to be brought into Sensus plenoir—a fuller sense—through the offering of simple attention.” – Lyanda Lynn Haupt, author and naturalist.

“…what would it mean for contemplative practice to be considered an integral part of a deepening ecological awareness?” – Theologian Douglas E. Christie, author of The Blue Sapphire of the Mind; Notes for a Contemplative Ecology

Sky Island Alliance Volunteer Log

Winter 2018 Visit to the Spring

The sun is shining but the wind blows bitter, chapping the skin on contact. Waves of wind curl the bleached grass, pressing it against the hillside.

On the way to the spring, we pass stands of fallen cactus: saguaro and prickly pear in a state of decay, crumbling under our feet to dust, reminding us of the importance of the season, death, and resurrection. We pass tall grey ocotillo, skinny standing bones, thorned, sentinels of winter in the desert.

Deer trails etch deeper into the hillside, revealing how fragile the surface of the desert really is. Trails created even once carve into the topsoil like scars on the skin. The only thing that soothes and sometimes removes the mark-making are the rains, scanty this year.

Though the grasslands are winter-dried and tamped down, tiny pokies with feral intelligence find their way into my socks and I need to stop, drop, and remove my shoes.

Dotting the trail like bread crumbs in a fairy tale: chunks of chalcedony milky quartz. Some resemble circular geodes broken open. Some have a vulva-like shape and are shaped like roses. I always think of them as Desert Roses though this term is actually associated with rocks created from gypsum. Common in the Sonoran Desert grasslands, chalcedony quartz pieces are a child’s ‘jewels’ of the desert.

I pick up a palm-size chalcedony desert rose and think about Tucson’s beloved “Pink Rose of the Desert,” the Benedictine monastery shuttered this year after 75-plus years gracing our region. The monastery was lived in and loved by the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, a contemplative order well-versed in the traditional Benedictine practice of Lectio among other charisms. Lectio (Latin for Divine reading), devotional listening with the ear of the heart, continues to inform my growing contemplative take on the natural world.

Sycamore leaves carpet the ground and float in the swollen spring waters.

Maple-like Arizona Sycamore leaves litter the hillside having blown up the slope from the spring. I pick one up and cup it in my hand. Fragile to the touch and dry as the desert air, it miraculously retained its shape, curled up like a starfish. From A Botanist’s Vocabulary, by Pell and Angell, I learn that in winter the leaf’s “acuminate” tapered points draw in toward the center, towards the “petiole,” where it connects to its stem. The pull to turn inward and draw down, to contract in the process of dying, untethers the now concave leaf, freeing it to chart a new course: a paper boat on the wind.

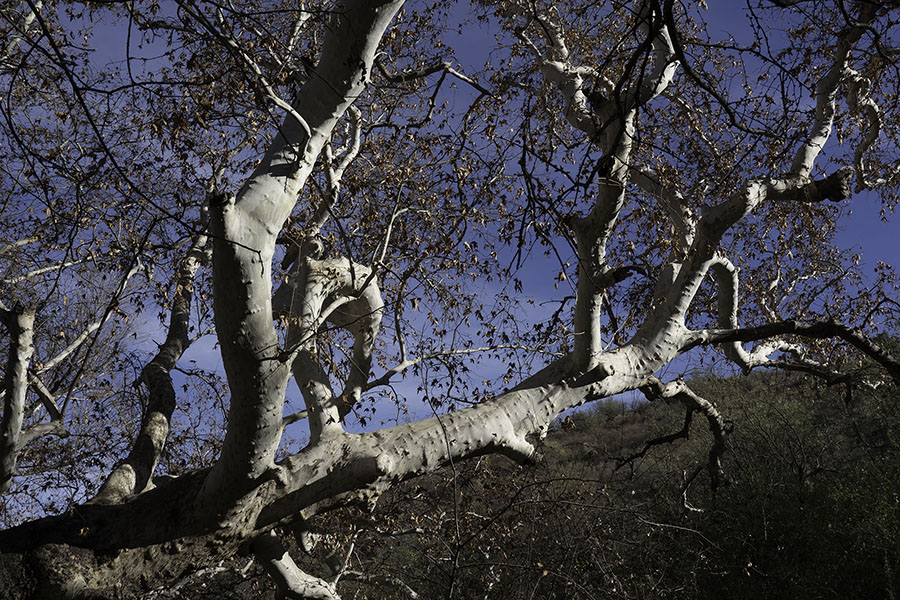

The first thing that jumps out as we approach the spring, almost assaulting the eye: bright white branches of the huge Arizona sycamores. Called ‘ghost trees” in winter, with their leaves stripped bare, they display an austere beauty, a natural authority over all other elements in the Spring. Next to them, the cottonwoods look shabby-chic like old heirloom lace.

Entering the spring, there is a sense of coming home. We hear naught but one single solitary bird: the dove mourning. The spirit of winter has officially abducted the spring. It is now an otherworldly destination, commanding solitude, silence, and peace.

In the center of playgrounds of leaf litter strewn all over the grounds—plugging even the badgers’ holes—we are astounded to see patches of lime green grass, asparagus-like shoots, dotting the grounds like candles on a cake.

There’s more water here than we’ve ever seen!” Steph exclaims. Black soil gushes under our feet with each step. Showers in the mountains above, rain unseen, must have fed the underground waters.

Higher than the known top of the seep, giant round balls of deer grass can only mean one thing: A new water source. We watch with awe as water flows down the entire valley of the spring, sparkling in narrow shafts of sunlight beaming through the canopy.

Tarzan’s Tree

Tarzan’s Tree still stands proud, bare of leaves for winter.

Last summer, our first time at the spring, Steph and I, along with Sami Hammer, Conservation Biologist at Sky Island Alliance and our guide that day, nicknamed the largest Sycamore, Tarzan’s Tree.

Sycamore tree trunks grow wider than any other hardwood in North America, and this tree is no exception, measuring a good 4 ½ feet in diameter. The tree must weigh in the thousands of pounds. Tarzan’s tree cantilevers over the middle pool of the spring, its huge exposed roots gripping the bank like the tentacles of an octopus squeezing its prey. We sit on the ground, our backs tucked up against the roots, and marvel at the improbability of its ongoing horizontal survival: Is the tree growing toward the water or the light?

We estimate the sycamore to be upwards of 200 years old. Water-loving sycamores are some of the oldest trees on earth and noted for their longevity (500 – 600 years in some cases). After 200 years, the tree rots inside and hollows out, but lives on, ensuring nest sites for elegant trogons, owls, and many other birds. The spring’s ecological zone is flush with the stately elders.

Sycamores figure prominently in history, from Hippocrates to the Ancient Egyptians, and in literature, like the poetry of William Carlos Williams’ Young Sycamore and in the Bible: I was neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet, but I was a shepherd, and I took care of Sycamore-fig trees. – Amos 7:14

Here in the Sonoran Desert, we must be the shepherds, the stewards of all plants and pollinators and natural springs critical to wildlife corridors on both sides of the International border.

Douglas Christie finds parallels between naturalists in the tradition of John Muir and Thoreau, and scientists: “…the way they have trained themselves to gaze at the world and the language they use to describe their experience of the natural world… One can find “a deeply contemplative sensibility that reveals a reverence and even a love for a world not often accounted for by the limited vocabulary of science.”

Delicate shoots of green sprout from the spring’s life-giving waters.

The reverence gained in my own winter of years does not escape me. It is here in the spring, that I feel most congruent with the cycle of seasons, with life and death, the fecund dark, and life-giving light. After Fall, in the great pause of winter, the animals, the land, our bodies, and our souls, are granted the balm of contemplative rest.

The sun begins to slip behind the mountains and the temperature drops fast. It’s in the low 40s now. We are expecting a freeze tonight and we still have to measure the spring’s all-important water flow: an entire liter of fresh clear water in 5.25 seconds! My fingers, wet and starting to freeze tell me it’s time to go.

As for our mystery: the softest plant ever, we found its young shoots again and photographed them. Later research leads us to believe they are saplings of Velvet Ash, native to Arizona. The velvet ash tree can grow up to 40 feet tall in riparian habitats, its leaves velvety only while young.

Read the first installment of Val’s Volunteer Log from summer 2017.

Read the second installment of Val’s Volunteer Log from monsoon season 2017.

Read the third installment of Val’s Volunteer Log from fall 2017.

All photographs by Stephanie Stayton & Valarie Lee James

www.ArtandFaithintheDesert.wordpress.com

Note to the Reader: the whereabouts of this wilderness spring is not revealed to ensure the survival of its unique ecosystem.